On March 19, 2007, the weather in the south of Armenia was terrible: there was a strong wind and a snowstorm. As it is said in Armenia, it was a typical “mad March”. The mad weather threatened to disrupt the grand opening of the project, the first talks about the prospects of implementation of which launched back in 1993, when the first Artsakh war was still going on.

The ceremony of commissioning the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline scheduled for the morning of March 19 with the participation of the presidents of the two countries, was postponed. Due to the weather conditions, the helicopter was unable to transport Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to Meghri and instead landed in the Iranian city of Julfa, from where, the President of Iran headed to Meghri by car.

Finally, at 2:05 pm, the presidents of Armenia and Iran Robert Kocharian and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad opened the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline. Because of the bad weather, no speeches were delivered at the official opening ceremony.

Today we will talk about how the gas pipeline project was implemented, what transformations it went through, and also present the broader geopolitical context. The latter is especially interesting to consider through the prism of the situation Armenia found itself in after its defeat in the war of 2020.

Potential transit, Ukraine and Georgia

In the early 2000s, Yerevan viewed the gas pipeline project as a potential transit one.

Armenian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Ara Papyan said in an interview with Iravunk newspaper in 2000 that there were three main problems hindering the start of the project:

- lack of funds to start construction;

- the price of Iranian gas;

- the unwillingness of the Iranian side to supply gas to Armenia all year round.

Iranian gas was more expensive than Russian gas, and this might lead to sales problems, Papyan was saying. He noted that Ukraine had repeatedly expressed its interest in the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline project. “But if the price of Iranian gas is twice as high as the price of Russian gas, of course, Ukraine will refuse to buy it,” Papyan noted.

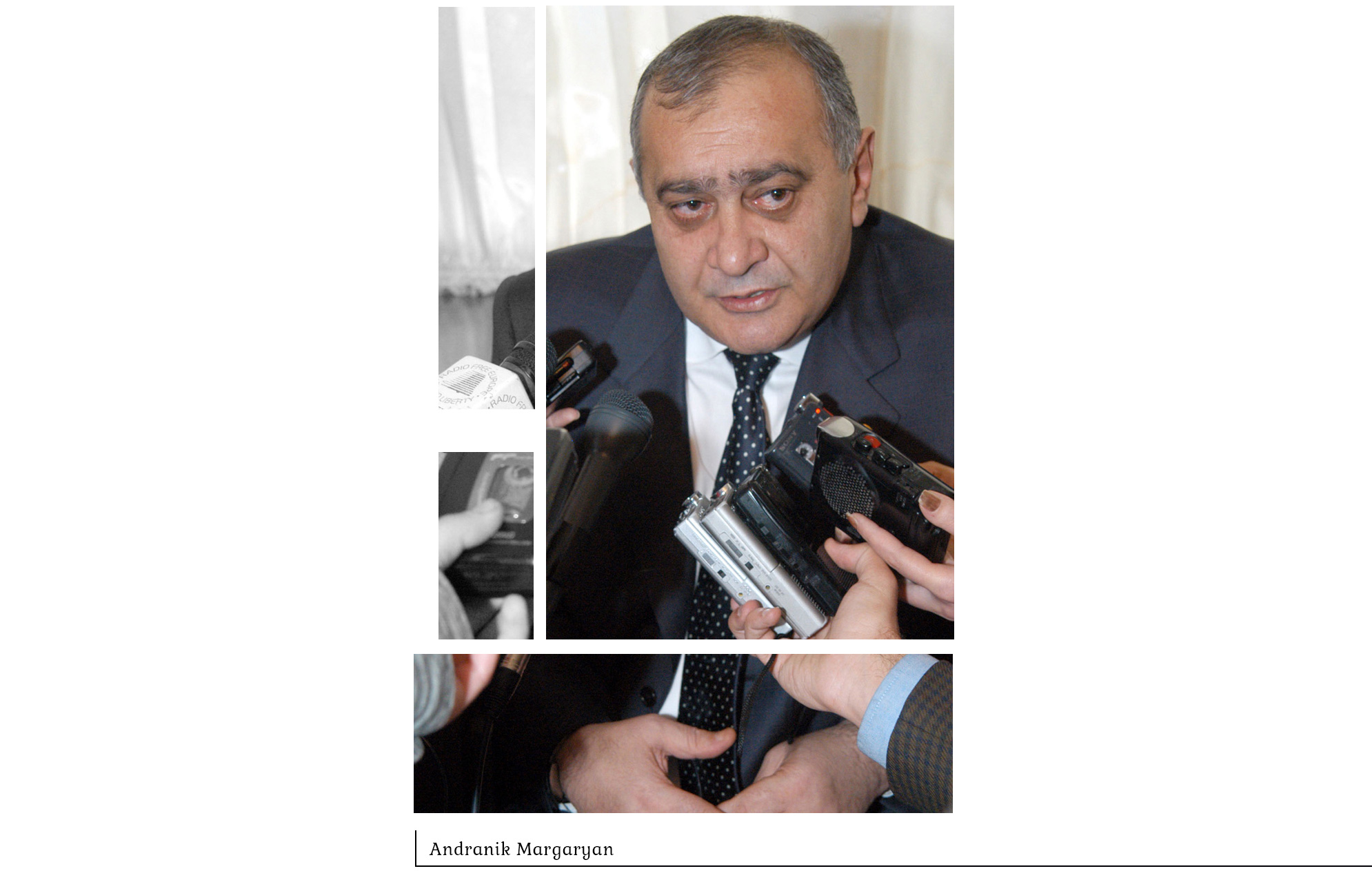

Ukraine first showed interest in the gas pipeline project in 1999 when Armenia’s foreign minister visited Kyiv. In June 2000, at a meeting with Ukrainian Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko, Armenian Prime Minister Andranik Margaryan officially voiced Yerevan’s desire to see Ukraine among Armenia’s partners in the construction of the gas pipeline.

However, the issue of price remained a key one. “If the price turns out to be acceptable for us, we will take an active part in the implementation of this project,” Deputy Foreign Minister of Ukraine Dmitry Tkach said in an interview with Mediamax.

Armenian diplomats said Georgia’s consent to the further passage of the gas pipeline through its territory in the direction of Europe was also important. Tbilisi showed little enthusiasm, which made the chances of participation of the European Union and international financial institutions in the project miserable.

The piquancy of the situation was that one of the main reasons for Yerevan’s interest in the project was that Armenia received natural gas only from the territory of Georgia, and in the event of any force majeure situations there, the prospect of a complete deprivation of gas supply seemed more than real.

“Don’t confuse the Caucasus with the Caribbean.”

Yerevan and Tehran had to object to the United States, which did not hide its negative attitude towards the plans to build a gas pipeline.

“For us the construction of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline is a way to look for alternative energy sources, and I have a negative attitude toward any attempts to interfere in this process,” Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian said in spring 2000.

Tehran’s reaction was predictably tougher. “Statements by U.S. officials are made without regard to the political and economic independence of the countries of the region and oppose the development of economic cooperation and free market relations. Forces located in some distant countries confuse the Caucasus with the Caribbean,” the Iranian embassy in Armenia said in a statement.

Despite the negative attitude to the project, the U.S. refrained from harshly critical statements in the following years. Most likely, Washington realized that Iranian gas was Armenia’s only alternative to Russian gas.

The Turkmen gas factor

On November 29, 2000 the Armenian president paid a one-day visit to Turkmenistan. The official sources in every possible way concealed from the media the fact that the issue of possible supplies of Turkmen gas to Armenia through the territory of Iran was discussed at the meeting of Presidents Robert Kocharian and Saparmurat Niyazov.

Opinions were then voiced that the supply of Turkmen gas to Armenia through the territory of Iran could be the only way to save the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline project from the prospect of being frozen.

The possibility of exporting cheaper gas from Turkmenistan to Armenia through Iran was considered back in the early 90s. It was believed that Turkmenistan could supply fuel via the current Korpeje-Kordkuy gas pipeline to Iran, which, in turn, would send gas to Armenia through Iran-Armenia gas pipeline.

“We want,” “we don’t want”

In May 2000, at a meeting with the President of Armenia, Alexander Pushkin, Deputy Chairman of the Board of Gazprom Directors, and Igor Makarov, President of the Itera International Corporation, spoke about the “high priority” of the construction of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline.

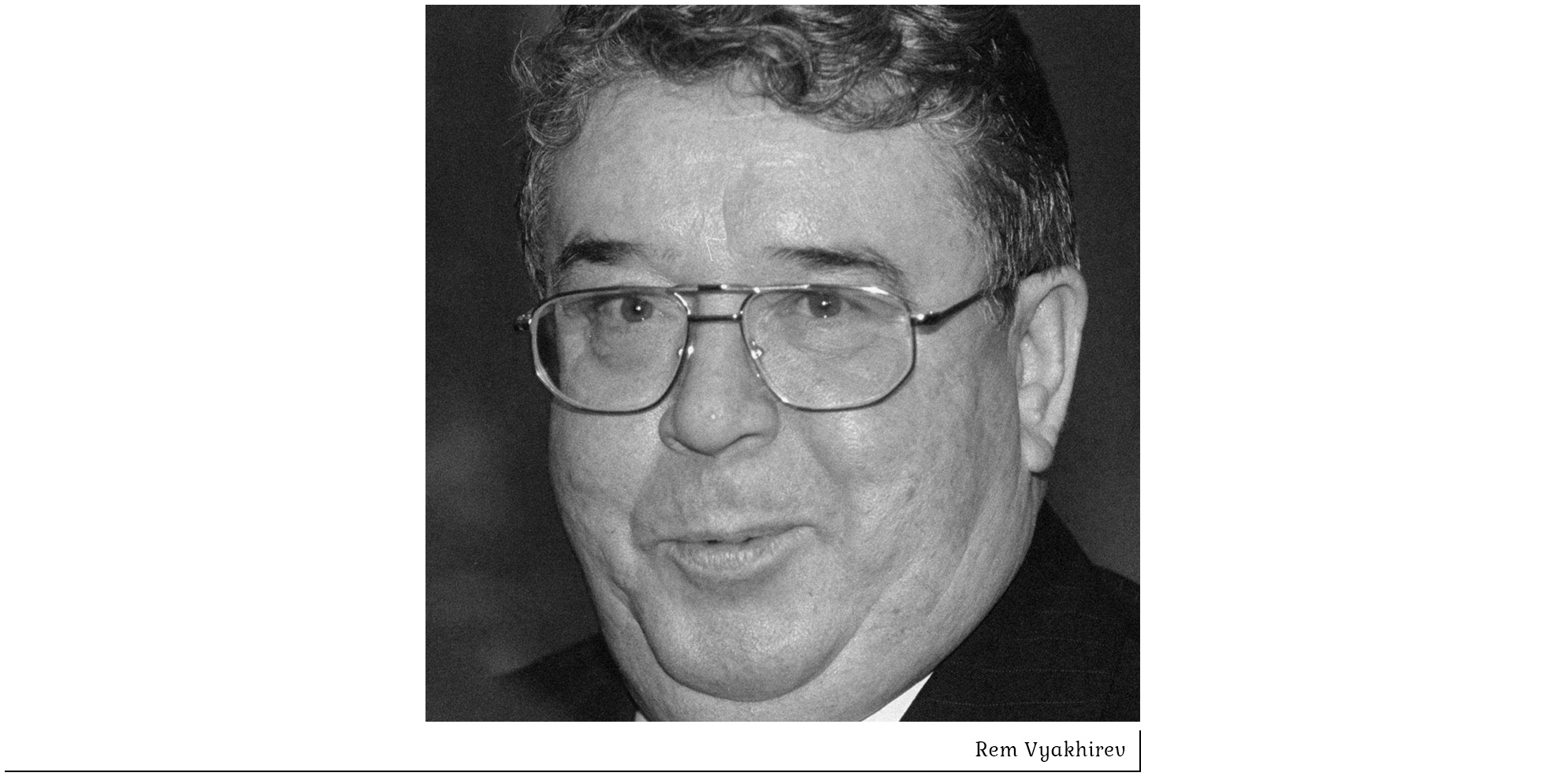

Information appeared in June that Gazprom and Itera were ready to take part in the project, but a few days later Gazprom Chairman Rem Vyakhirev said the company had no plans to participate in the construction of the pipeline.

Then Russian Deputy Prime Minister Ilya Klebanov arrived in Yerevan and announced that Gazprom would participate in the construction of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline. “We believe that this is a very important project for the economy of your country,” he said. In August 2000, another Russian Deputy Prime Minister, Viktor Khristenko, confirmed that Russia was “ready to consider its participation.”

A month later, during the September visit of Russian President Vladimir Putin to Yerevan, the leaders of Gazprom and Itera spoke about the “prematurity” of statements about their readiness to participate in the project.

What was signed in Tehran?

On November 15, 2001, the Armenian government approved the draft Armenian-Iranian agreement “On the Transit of Turkmen Gas to Armenia through the Territory of Iran,” which was expected to be signed in December during President Robert Kocharian’s official visit to Tehran.

At the end of the visit, it was announced that the parties had signed an agreement on the construction of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline. However, the specific content of the agreement was not presented to the public. Robert Kocharian said only that “the gas pipeline will be designed to meet Armenia’s needs.” This actually meant that Yerevan gave up the prospect of making the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline transit.

A year earlier, Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia had signed an agreement to transit Azerbaijani gas from the Shah Deniz gas field to Turkey, and it would have been strange for Tbilisi to participate in a competing project. The key, however, was Russia’s position, which sought to prevent the emergence of competing gas transit projects and did not want to lose “gas control” over the former Soviet republics.

Gazprom and Itera

The redistribution of property and spheres of influence in Russia, which began after Vladimir Putin came to power, began to have a direct impact on the issues of gas supplies to Armenia and the implementation of the Iranian gas pipeline project.

On January 29, 2002, Itera announced that it was going to cut the volume of gas supplied to Armenia almost threefold starting from February 1. Itera’s statement said that in violation of the agreements reached, Armenia had not repaid the debt and failed to pay for current gas supplies.

Aggressive PR, which accompanied Itera’s actions, was considered by many to be an attempt to “stand out” in front of the Russian leadership. This version was supported by the fact that Itera made this statement exactly during ArmRosGazprom head Karen Karapetyan’s visit to Moscow to resolve the existing problems.

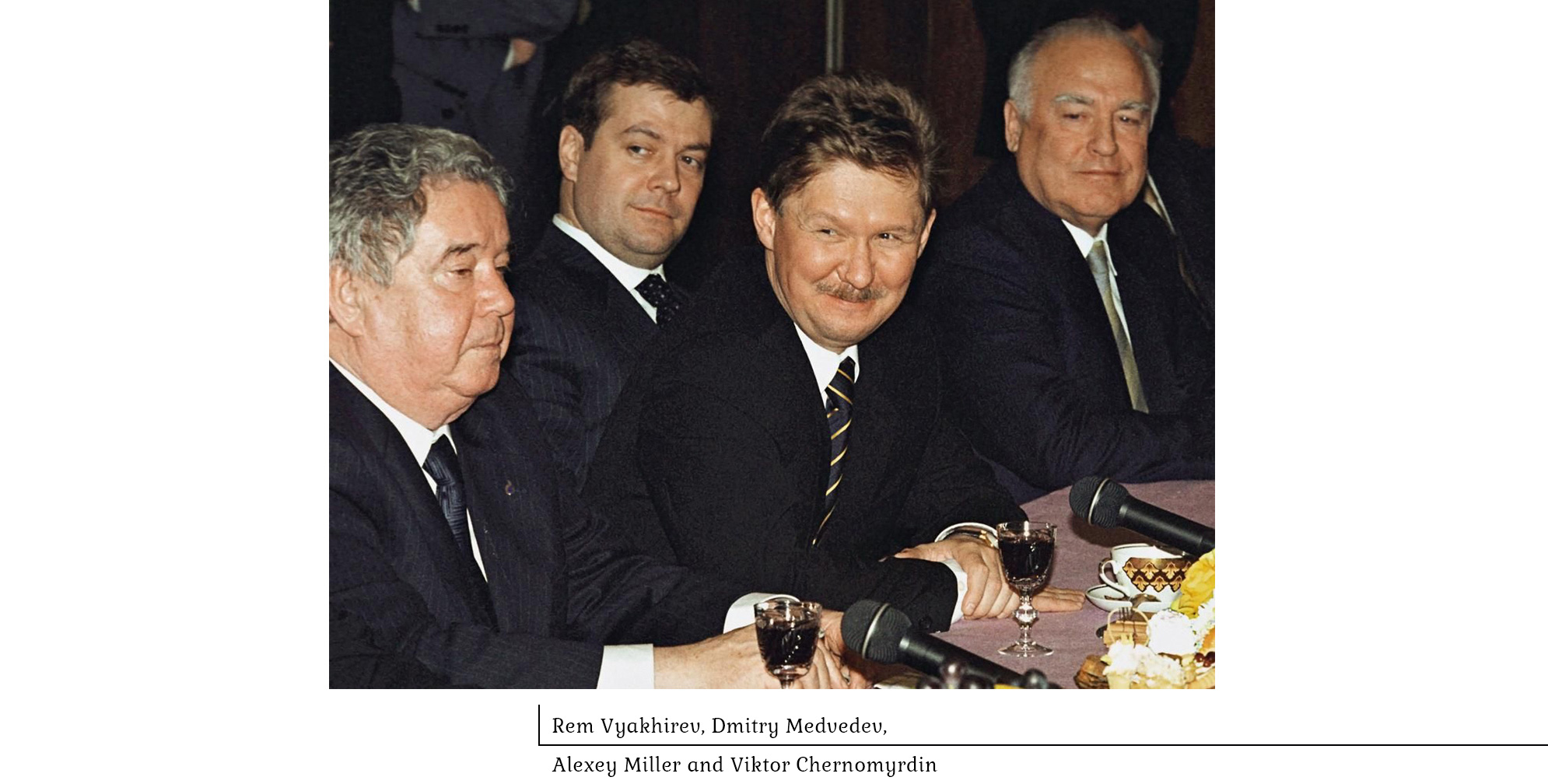

Even before Putin came to power, many Russian politicians and media had been wondering why Itera, which in fact was just a gas supply operator, was increasingly behaving as an independent political player. After Putin’s words “where is the money?” at one of the meetings on Gazprom, it became obvious that Itera’s “golden age” was passing.

On January 31, 2002, the Russian newspaper Vedomosti wrote citing its sources in the Russian government that the Russian cabinet instructed Gazprom to return the $126 million to Itera which it had paid for the Russian gas monopolist when establishing ArmRosGazprom – the Armenian-Russian joint venture.

Having paid $126 million for 45% shares in ArmRosGazprom, Itera was listed as the owner of 55% of the shares, while Gazprom received neither income from the transportation and sale of gas, nor dividends.

Vedomosti wrote that Armenian President Robert Kocharian, who paid a short working visit to Moscow on December 18, 2001, among other issues, discussed the above-mentioned situation with Chairman of Gazrpom Management Board Alexey Miller. According to the Russian newspaper, at the meeting a fundamental decision was made to return the Gazprom asset.

It is clear that the Armenian authorities preferred to deal with Gazprom, whose head Miller was considered “Putin’s man”, rather than Itera, whose patrons included the former head of Gazprom Rem Vyakhirev.

Belated offers

On March 11-12, 2005, Georgian Prime Minister Zurab Nogaideli paid an unscheduled visit to Armenia. What made the visit even more intriguing was his statement that the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline was one of the main topics of his talks in Yerevan.

“Of course, we are interested in ensuring that the gas pipeline built from Iran to Armenia will further serve to import gas to Georgia,” Noghaideli said. “It will be a profitable project for Armenia, and if today Georgia is a transit country for Armenia, then Armenia will become a transit state for Georgia,” the head of the Georgian government said.

His Armenian counterpart Andranik Margaryan was more restrained. “The Georgian side raised the issue of Armenia becoming a transit route for transporting gas from Iran through Armenia and Georgia to Ukraine. We heard this wish and will discuss it in the future,” the Armenian prime minister noted.

It seemed that the awakening interest of Ukraine and Georgia in the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline was primarily of a political nature. Mikhail Saakashvili and Viktor Yushchenko were actively trying on the role of leaders of democratic reforms in the post-Soviet space. In an effort to end their dependence on Russia, they considered all potential options for ensuring their energy security. Construction of the Armenian section of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline was supposed to begin in the next weeks, and the Georgian prime minister seemed to try to convince the Armenian authorities to increase the diameter of the pipe in anticipation of subsequent transit.

Alexander Ryazanov, Deputy Chairman of the Gazprom Board, who visited Yerevan in March, naturally, spoke out against the prospects for Iranian gas transit to Ukraine. He noted that both routes – Iran-Armenia-Georgia-Russia-Ukraine and Iran-Armenia-Georgia-Black Sea-Ukraine – discussed in the press valued at several billion dollars were economically unjustified.

“Become part of a new concept”

In April 2006, Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian stated that “Armenia intends to become part of the new Euro-Atlantic concept of energy security, which the US and the EU are actively working on.”

He said that while working on this concept “we are talking about new nuclear power plants, the construction of the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline, and all these discussions are of interest for Armenia.”

Later, Vartan Oskanian stated that “Armenia has set a goal to join the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline and has already started serious negotiations with the United States.” “If this project is implemented, Armenia will have three sources of gas supply: Russian, Iranian and Central Asian,” Oskanian noted.

In early 2007, the foreign minister confirmed Armenia’s interest in the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline project – “we are negotiating and trying to be involved in the processes related to this project.”

Azerbaijan cooled the ardor of the Armenian side.

“Armenia cannot negotiate about this with the US for a number of reasons. One of them is that no regional project is possible without Azerbaijan’s participation, either as an exporter or as a transit state. And we will consider cooperation with Armenia possible only after the settlement of the conflict and elimination of its consequences,” the official representative of the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry said.

“Some regret”

On January 23, 2006, spokesperson for the Armenian president Viktor Soghomonyan in an interview with Mediamax described as “untrue” the reports that the Armenian side offered Russia 45% shares in the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline in exchange for Gazprom not to raise Russian gas price during the year. The president’s spokesperson said that during the January 22 meeting of Armenian and Russian presidents Robert Kocharian and Vladimir Putin in Moscow, the sides discussed the issue of Russian gas supplies and agreed to continue negotiations.

Mediamax sources though said that there was no progress in the talks between Kocharian and Putin. “Russia’s proposal to hand over to it the fifth power unit of Hrazdan thermal power plant and the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline was and remains unacceptable for us,” the Armenian government said.

A day earlier, at the opening ceremony of the Year of Armenia in the Kremlin, Robert Kocharian said that “our partnership should be guided by the logic of long-term cooperation and be insured against the current conjuncture. He also asked the following question: “Aren’t we losing something very important from the inexorable globalization, fashionable multivectorism and pragmatism of the market?”

On January 24, Viktor Soghomonyan said that “the situation around Russian gas supplies to Armenia causes some regret. “Given the strategic nature of our relations with Russia, we hoped that the issue of determining the price of Russian gas could have been resolved more easily and not require such long negotiations,” he said. At the same time, the Armenian president’s spokesperson stipulated that “cooperation with Russia in the energy sector is only one of components of our strategic partnership and cannot be a reason for reviewing the entire range of relations. However, Viktor Soghomonyan did not rule out that “the energy component of the Armenian-Russian cooperation will be revised.”

“In the current situation, we are more concerned with the formation of a public opinion in Armenia, which can hardly be considered favorable for Russia. We worry that such public sentiments may be decisive in the long run,” the spokesperson for the Armenian president said.

And Armenian Defense Minister Serzh Sargsyan, who was considered Robert Kocharian’s successor, said that “an increase in the price of Russian gas, even if it takes place, cannot serve as a reason for reconsidering the agreement on deployment of the Russian military base in Armenia.”

At the same time, he noted that “the gas problem is not purely economic issue, there is a problem of trust, and not only trust, but also of those things that are usually not being discussed publicly.”

Already on March 22, Serzh Sargsyan, who was also the co-chairman of the Armenian-Russian Intergovernmental Commission, stated that the price of Russian gas for Armenia might be lower than the announced $110 per thousand cubic meters.

Soon, the “compensation mechanisms” designed to mitigate the consequences of the Russian gas price hike for Armenia finally became public.

On April 6, Gazprom issued a press release announcing the signing of a “long-term agreement for a period of 25 years with the Armenian government which defined the strategic principles of cooperation.”

“Gazprom announced that under the agreement, ArmRosgazprom, 45% of shares of which is owned by the Russian giant, will buy from the Armenian government the 5th unfinished power unit of Hrazdan TPP (Hrazdan-5) and the first 40-kilometer section of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline, which was under construction. According to the signed agreement, ArmRosGazprom was to complete and upgrade Hrazdan-5. The press release noted that “upon completion of the deal, Gazprom’s share in the authorized capital of ArmRosGazprom would constitute a qualified majority.”

The Armenian-Russian agreement stipulated that the price of Russian gas for Armenia would remain $110 per 1,000 cubic meters until January 1, 2009.

The Armenian government issued a press release on April 6 stating that Hrazdan-5 would be sold for $248.8 million and that in addition, Gazprom would invest $140 million to modernize the power unit.

The Armenian government’s news release did not say anything about the sale of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline section. It became known that two hours after dissemination of its press release, Gazprom applied to media, asking not to use it and wait for a new version.

The Iran-Armenia pipeline was no longer mentioned in it. Nevertheless, Vedomosti’s sources in Gazprom claimed that the agreement to purchase the pipeline had been “reached, but not yet formalized.”

Sources in the Armenian Foreign Ministry said that in January 2006, when the media first reported that Armenia had agreed to sell to Russia Hrazdan-5 and part of the pipeline, Tehran reacted extremely nervously, and Armenian diplomats had to work hard to calm down their southern neighbor.

New situation

Early 2007 marked the beginning of a new energy situation in the South Caucasus.

What happened?

1. Azerbaijan refused to buy Russian gas and use the Russian pipeline to export its oil.

2. Georgia began to buy Russian gas at a price of $230, which Tbilisi called “political”, but the Georgian authorities said that they would refuse Gazprom’s services as soon as the volume of Azerbaijani gas supplies became sufficient.

3. It was officially announced that the 40-kilometer section of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline would be handed over to ArmRosGazprom’s management.

“When “Gazprom” does not manage to reach its aim by using the stick and the carrot policy, it just pushes its way through, just as it did in Armenia, where it bought up the entire local energy infrastructure not to give Iran the possibility to compete with it for the supplies to Europe”.

The most significant of the above-mentioned was Azerbaijan’s refusal to buy gas from Gazprom and the way in which official Baku presented its decision.

On December 23, 2006, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev said in an interview with the Ekho Moskvy radio station:

“When we started buying Russian gas, the price for it was on the level of $48. At that time, the “ITERA” Company was the one involved in the process. We had a long-term contract with that Company, and we were content with the given contract. Afterwards, the supplier changed, owing to circumstances beyond our control. Now the supplier was “Gazprom”, with which there was a 5-year contract signed. There was a fixed price at the sum of, as far as I remember, $55 of $60 for one thousand cubic meters. “Gazprom” annulated the contract by a unilateral decision last year. In other words, “Gazprom” made it clear that it is not going to supply gas for the given price. Therefore, the price for the gas was set to be $110. We agreed, although it was odd – for all that, it was a 5-year international engagement of a large company. In 1994, we signed the “Contract of the Century” with foreign companies, and not a single comma has been changed in those contracts. We think that trust should be earned through years. Moreover, it can be lost because of one singe wrong step. However, evidently this approach is not true for everyone. Despite the breach of obligations, we, showing good will and cooperation spirit, agreed to the $110 price.

However, when the price increased to $230 and, the last moment, to 235, here, of course, one feels the complete dissonance of the given approach with the spirit, the character and the essence of the Russian-Azerbaijani relations. In addition, this arouses regret, as our relations we are developing in a very positive, constructive manner. Those relations cover much larger spheres, than mere energy. And if the issue is energy, especially gas, later on it would be, probably, more logical and wise to search for common grounds for joint activities, joint projects, rather than to try increasing the price, based on unilateral decision, and thus, to some degree, try to force Azerbaijan to accept it. This is impossible. Azerbaijan is already not the country, which can be forced to do something. On the other hand, this is their right: “Gazprom” can make the price for gas even $500 or $1000. It has the right to do so, just as we have the right to refuse.”

“Gazprom” uses forestalling on other markets as well – for example, in the Caucasus, where the Kremlin did everything possible not to let Iran gain the possibility to establish an infrastructure, which would allow it becoming a competitive supplier to Europe. Not to let the Iranian gas penetrate the European market, Russia bought the entire energy sector of Armenia.”

The “Protect us Against Bullies” article of the Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov, published on January 19, 2007 in The Wall Street Journal, proved that Aliyev’s statements were not just a splash of emotions, but the new policy of Baku.

“Practically in a moment the price for gas increased twice for us. It is something more than just a mere signal of the market, and it is unacceptable for Azerbaijan. As a response, we decided not to buy the Russian gas, as well as to stop using the Russian oil-pipeline for the export of the Azerbaijani oil to Europe. This is a determining moment for Azerbaijan and the whole South Caucasus. Azerbaijan sincerely wishes to have pragmatic relations with Russia, based on market principles, however, being an independent state, we are guided by our own national interests,” the Azerbaijani foreign minister stated.

In early 2007, commenting on the statements made by Aliyev and Mammadyarov, I wrote:

“Last year Azerbaijan was using the energy services of Russia, and today, it decided to refuse using them. This means that one of the key factors of Russia’s influence on Azerbaijan is henceforth lost, and this, undoubtedly, will influence the process of the Karabakh conflict settlement. We just hope that the Armenian leaders will seriously analyze this circumstance.”

Unfortunately, these hopes were in vain.

Ara Tadevosyan